Faerie News

Faerie News

Dr Rebecca-Anne Do Rozario published her book: Fashion in the Fairy Tale Tradition: What Cinderella Wore (Springer, 2018). A journey through the fairy-tale wardrobe, from glass slippers to red shoes, capes, bonnets and glittering gowns, it explores how the mercurial nature of fashion has shaped and transformed the Western fairy-tale tradition. Unveil patronage, intrigue, privilege and sexual politics behind the most irrepressible, irresistible fairy tales!

Rachel Nightingale published her novel Columbine’s Tale on Odyssey Books. Rachel is a writer, playwright, educator and actor. With a passion for storytelling and theatre, it was natural her first fantasy series would feature both!

Review

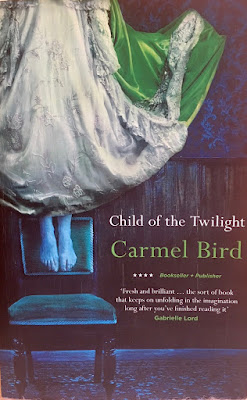

Child of the Twilight - a novel by Carmel Bird

Review by Louisa John-Krol, Winter 2018

Carmel Bird adores words. She plays with them like a cat with prey, letting them float and fly before pouncing on them, then letting them run off, knowing she can catch them again, yet ready with a nonchalant shrug if they escape, never to return. If they soar far above, or lurk in cryptic nooks and crannies of perception, all the better.

In the foreground is a banquet of alliteration: ‘Round and Round the rugged rocks the ragged Rascal ran’, a reference to folk tunes like ‘The Gypsy Rover’ or nursery ditty of Mother Duck, ‘over the hills and faraway’ (p.81), revisited with Shakespearean puckish magic ‘over hill, over dale, over those hills and faraway’ (p.172). There’s a generous dose of assonance, with ‘the glass-blowers of Murano and the lace-making on Burano’ (p.192) and ‘Humble-Bumble, Hocus Pocus’ (in the eighth chapter title). Nursery-rhyme playfulness with Little Boy Blue (p.134), Pudding and Pie (again, eighth chapter title) or ‘Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross, to see a fine lady upon a white horse’, gives the narrative a medieval sparkle, like stars on a Flemish Limbourg sky - the kind on the interior of a dome that Montaigne, that great French essayist, might have gazed up at from his bed - or the pert oranges in a pre-Raphaelite orchard. Or, for that matter, the beading on the gown in Samantha Everton’s 2009 photograph ‘Chrysalis’ gracing my edition of this novel; an eerie quality of this picture is the illogical logic, or logical illogic, of perspective in the positioning of blue feet on a chair’s inner back of brocaded velvet. Samantha Everton's website is worth a visit.

|

| cover photo by Samantha Everton |

In the middle-ground flows the fluidity of Furta Sacra, which rings to me like sacred furtiveness: the ability of a statue to choose when it moves from one site to another. Whether it travels via theft, purchase, miraculous translation or postage (disguised for its own protection), slumbers beneath waves or hides in plain sight beneath an auction house, it has an uncanny knack of shifting itself around. Furta Sacra was invoked in the Middle Ages, ‘the hey day of relics’ (p.34) to explain the ‘movement’ of statues. The focal point of this pageant is Bambinello, the Infant Jesus to which women pray for fertility, or for protection of their babes, in the Franciscan church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli. Bird’s description of the Bamb (as the narrator affectionately calls him) would sit happily in an old French or Italian fairy tale: in 1892, when Rome suffered an epidemic of typhoid, Prince Alessandro Torlonia lent his gilt coach for the Bambinello to travel in, drawn by a pair of chestnut ponies and ‘driven by coachman in blue livery with silver braid’… The baroque surface of the coach was knobbed, embossed, curlicued, feathered, fanned, flowered all over. High on its topknot was a golden cross on a gleaming globe’ (pp 23-24). It’s not only the Bamb who goes missing. It’s a baby-bunting, missing from the arms of a little cherry-wood statue called Le Sourire (The Smile), also known as La Souris (The Mouse), embracing the air as if her child is still ‘smiling-dimpling’ up at her, long after she was found floating in a spring. Other statues march through the book, such as the Infant of Prague, enabling the Bamb to operate in a chamber of echoes, as if the story itself were a crypt or cavern.

Around it all is the frame of a young woman, Sydney Peony Kent, grappling with the mystery of her adoption, ruminating on possibilities of her ancestry, collecting diaries or letters of the deceased, and exposing twin pillars of fertility and infertility that spin a turn-table (a metaphor for The Wheel of Fate?) at a convent, Le Sourire. Upon this dias, grieving mothers place their dead babes, only to receive living ones from nuns presiding over births of the unwillingly pregnant, cloistered within. No need for cynicism here. It matters little whether these mothers believed the infants ‘returned’ were their own - miraculously restored - or at some level guessed the trickery; the magic is in the sheer practicality of it all, the bizarre logic, the deftness at solving problems at both ends.

Over it all hangs an atmosphere of breathless, soulful suspense. Not the kind one finds in a slick plot stuffed with action, but the musing that hovers in a private, ‘perpetual shrine’ of remembrance to a dead child. Or a crypt of statues, as in the Chapelle des Enfants. Or generations of marionettes hanging from a ceiling of Le Théâtre Royal de Toone, clay feet dangling, faces poised, rapt, watching shows go on beyond their dancing days. Or the patience of a kingfisher in a pool. Or the waiting of sylphs in tree-boughs, ready to swoop across a field of lavender and swags of poppies in Woodpecker Point, Tasmania. Or a valley of forget-me-nots between towns like Olinda, Emerald or Sassafras in the Dandenong Ranges.

Poetic prose hovers near the edge of surrealism and magic-realism, but never quite slips over into fully fledged psychedelia, adhering to the more stately iconography of European art history and global Catholicism, especially Italian, Irish and a diaspora of both.

Poetic prose hovers near the edge of surrealism and magic-realism, but never quite slips over into fully fledged psychedelia, adhering to the more stately iconography of European art history and global Catholicism, especially Italian, Irish and a diaspora of both.  |

| Book Wizard with Pentacle - photo by Louisa John-Krol |

|

| Primavera by Sandro Botticelli |

Among these literary gems, Bird scatters pearls from Fine Arts, with such natural flair that Veronica’s ‘titian curls’ don’t warrant a capital T; the great painter’s name settles into the prose as a casual adjective. One imagines the word reclining nude, stretching its legs. Bird’s visual tributes range from overt appraisals to subtle hints, an example of the latter being the skin of a pomegranate ‘ripe upon the branch’ (p.59), a charming simile reminding me of the legendary fruit man motif, which the self-portrait by Arcimboldo depicted in the 16th century. Bird also cites a Chinese painter Claude Zhang and a Spanish station, Perpignan, that Salvadore Dali considered the centre of the world. Architectural features are lovingly outlined, such as wooden finials, fascia boards and gules in an early nineteenth century colonial Tasmanian mansion. (I had to look up the definition of ‘gules’. Besides the alliterative glee of googling gules, I learned that they are bands of red colour shaped like a heraldic shield. Paired with coinspots in Bird’s description, they are painted glass.) Rosita, apropos the author Lorca, was nick-named Flora-n’-Fauna for the botanical focus of her drawing and painting, weaving her with Botticelli’s Primavera, one of my favourite paintings of any era, anywhere. Like one of Bird’s travellers Diana, I too wept before that painting and its twin, Birth of Venus, which when I visited the Uffizi in Firenze during 2003 were positioned in the same small room, so that their beauty enfolded one like two giant wings. Their size was overwhelming compared with seeing them in miniature, in books or postcards; it was as if their frames were windows, through which one gazed at an orchard with real people strolling only a cooee away. If we threw an apple core out of that imaginary opening, one those figures might catch it. As I watched them, music - ‘Trittico Botticelliano’ (Three Botticelli Pictures) by Respighi played in my memory, in gusts of scented blossom. Then there was Cora’s wedding scene, in which her green gown evoked a painting of the marriage of the Arnolfinis, and another entitled May in the medieval Book of Hours for the Duc de Berry.

|

| Apple picking fairy, Image Graphics |

Ah yes, there is music in this novel, like zampognari (bagpipists) and pifferai (flautists), along with the song of birds, true to our author’s surname. When a couple in the tale make love, they play a CD of a violin concerto by Vivaldi. I love her phrase ‘troubadour green language’, the language of birds, which Cosimo acquires from drinking the blood of dragons (pp.67-68). There is delight in musicality of language, as in doucement, doucement (slowly, slowly), to describe the arrival of a mysterious ship at Boulogne-sur-Mer, after losing all its crew but for The Black Madonna; or in mingling Italian and Irish accents. Bird sets up historical echoes, such as the British convict ship Amphitrite, burning and blown off course years later near the aforementioned French town, whose fishing boats and beaches would come to bear witness to mines of war (pp.74, 81). Music by Sibelius, Language of the Birds, plays at Cora’s wedding. Cora the Fertile is, I assume, a personification of the deity Kora.

|

| Antique book photo by Louisa |

In particular, I love Bird’s cheeky tone. Or more specifically that of her narrator Sydney, in her asides with the reader. Here’s my favourite: ‘I have earlier drawn attention to the letter motif in literature, and like a postman I will now deliver. Reader, You’ve Got Mail.’ (p.239) The reader is addressed again further within Roland’s letter, as if the author’s finger penetrates the Fourth Wall twice, through a double layer of fabric: ‘May I take you back to that rainy night…?’ (p.241).

The ensuing lines by Bird’s character Roland are supremely eloquent: ‘I am flooded with thoughts of the dangerous quest and of the malevolent guide, seeing myself as that guide, and I am occasionally overwhelmed with the spectre of blind meaninglessness and the wasteland that is my soul’s country’ (p.242).

|

| 'Hot Air Balloon' by Lorena Carrington |

|

| 1592 Pied Piper painting copied from glass window of Marktkirche, Hamelin |

The following was my own faery prayer for the boys and their rescuers:

Please Phra Pirun, have mercy. Hold back the floods. May sharp, slippery rocks be sentries, not demons in the dark. Bambinello, please bless the waiting parents. Kora, Flora, Inanna, all ye goddesses, please bring the children home, and their brave cave divers. For families of those who perish in floods or other terrors, may the Grief of the Ages be bearable, like the invisible infant in the cradle-arms of Le Sourire. May children of refugees find their parents, too. May all those who cross borders seeking refuge find welcome. Fairies, elementals, guides, let us unite. May our kisses rain, swirl and dance like cherry blossom. Spirits of apple and amber, please help our broken humanity to heal. Let there be a homecoming for our human tribe. Hooyah!

- Louisa John-Krol, Tuesday evening Eastern Standard Time, 10th July 2018

Carmel Bird is an internationally acclaimed Australian author.

Her novel Child of the Twilight, reviewed above, won the 2016 Patrick White Award.

|

| Carmel Bird, photo by Grant Kennedy |